Sanaz Koosha

Scientist, Flow Cytometry

Minimal/Measurable Residual Disease (MRD): From Hidden Reservoirs to Precision Biomarker

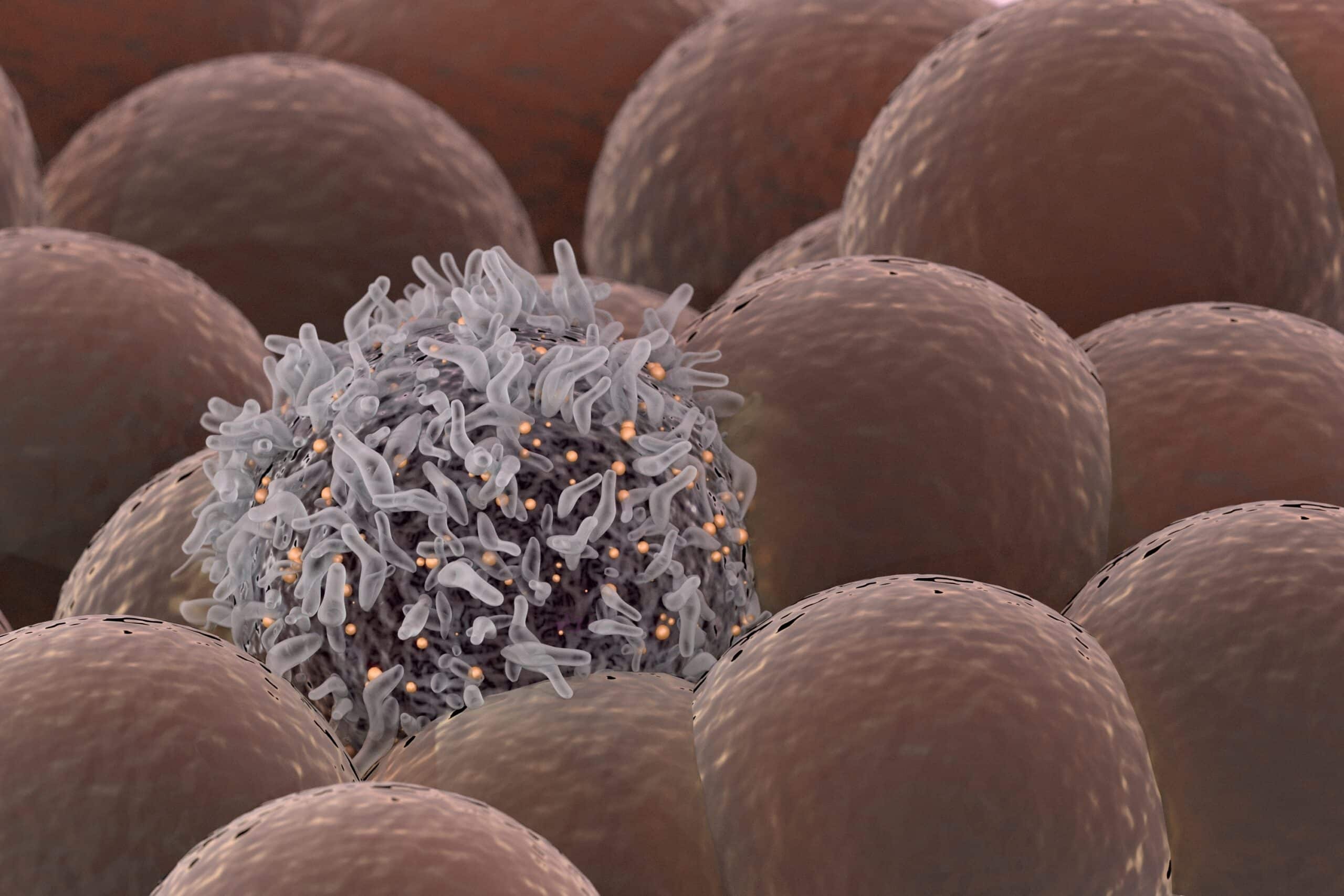

For decades, oncologists have grappled with a paradox: patients who appear to be in full morphologic remission may nevertheless relapse months or years later. The culprit is now widely recognized: a small number of malignant cells that survive treatment, lying below the detection threshold of conventional methods of detection, such as microscopy and cytology. These residual malignant cells, though invisible and scarce, have the capacity to repopulate and drive disease recurrence. It is from this observation that the concept of minimal (or measurable) residual disease (MRD) has emerged.

In this blog post, we will explore the key role that flow cytometry plays in assessing MRD in clinical practice, as well as some of the principles to keep in mind when creating a flow cytometry (FCM) assay for MRD detection.

The Rise of MRD: From Bench to Bedside

In hematologic malignancies such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) or acute myeloid leukemia (AML), MRD is typically defined as the proportion of leukemic cells remaining after therapy in bone marrow, or occasionally in peripheral blood, often at the levels of 10⁻⁴ (0.01%, or 1 leukemic cell in 10,000 healthy cells) or 10⁻⁵ (0.001%, or 1 leukemic cell in 100,000 healthy cells).

These cut-offs, while seemingly arbitrary, have been found to be useful metrics in guiding treatment decisions, influencing whether therapy should continue, intensify, or stop. In multiple myeloma (MM), being MRD-negative by FCM lowers the risk of disease progression by 80–90%. In AML, being MRD-positive by FCM is linked to a higher chance of relapses and shorter survival. When a patient remains MRD-positive after induction or consolidation, clinicians may intensify treatment, move to stem cell transplant, or add maintenance therapy. When a patient remains MRD-negative (determined by high-sensitivity assay), treatment may be reduced, lowering side effects, costs, and monitoring needs1.

The first systematic studies of MRD were conducted in the late 1980s and early 1990s at academic research institutions such as St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Investigators such as Giuseppe Campana and Ching-Hon Pui demonstrated that patients in apparent complete remission still harbored residual leukemic cells detectable by sensitive assays and that the presence of such cells strongly correlated with relapse3. Researchers and clinicians built on these insights and transformed MRD from a laboratory phenomenon into a prognostically useful biomarker.

Today, the detection of MRD has become integral to therapeutic decision-making, especially in the clinical settings of B-ALL and MM. Regulatory authorities — such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) — now accept MRD as a valid surrogate endpoint in clinical trials of new therapies for these diseases, accelerating drug development and approval.

The Central Role of Flow Cytometry in MRD Detection

Detecting such low-frequency events demands highly sensitive assays such as FCM, PCR, and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Among these, multiparametric flow cytometry is one of the most widely used methods for MRD detection because it is broadly available in clinical laboratories, can be performed rapidly, and directly profiles protein expression at the single-cell level rather than inferring it from DNA sequences4. However, one of flow cytometry’s greatest strengths is its broad applicability across different patient types. Unlike PCR or NGS, FCM doesn’t need a known genetic target to effectively detect cancer cells. Instead, FCM assays are designed to identify unusual patterns of protein expression markers on the surface of cells, using a “difference from normal” approach. Because of that, FCM can be used even when no tumor-specific molecular marker is available, like in newly diagnosed patients or diseases driven by many different mutations.

Still, FCM isn’t perfect. It works best with fresh, high-quality samples since cells need to stay alive and keep their surface markers intact. It also requires skilled experts or advanced software to interpret the results. Lastly, FCM-based MRD testing works better for some diseases than others. It works best in B-ALL, where standardized panels detect rare residual cells with high accuracy, making MRD a strong guide for treatment decisions and outcome prediction. In MM, it remains powerful but can miss disease due to patchy bone marrow sampling or extramedullary spread. FCM is challenging in AML because of variable antigen expression and overlap with normal regenerating cells1.

Recognizing these limitations helps set the stage for understanding the key steps in FCM-based MRD analysis.

From Sample to Reporting: Key Steps in Flow-Based MRD

Let’s go step by step through how MRD is assessed using FCM and highlight what really drives its sensitivity, consistency, and clinical impact.

- Panel Design

The selection of the antibody/fluorochrome combination is critical in panel design. Every FCM-based MRD panel starts with backbone markers that map the hematopoietic landscape, such as CD45, CD34/CD38, CD19 and CD3. Onto this framework, disease-specific markers are layered to uncover aberrancies, for example:

- In B-ALL, markers such as CD10, CD20, CD58, CD81, CD73, and sometimes CD13 or CD33 are used to identify abnormal B cells.

- In AML, markers like CD117, CD123, CD133, and occasionally CD7 or CD19 are applied to detect abnormal myeloid cells.

- In MM, CD38, CD138, CD56, CD19, CD81, and light chains κ/λ are used to define abnormal plasma cells.

Through a well-designed panel, rare malignant cells can be detected among millions of normal cells.

- Performance of the panel

To achieve this detection in practice, we need to test and understand the limits of our assay, or its sensitivity.

The sensitivity of an MRD assay depends on two core measures: the Lower Limit of Detection (LLoD) and the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLoQ). LLoD is the highest signal observed in the absence of the marker for a specific cell population in the assay; in other words, the smallest number of abnormal cells that can be distinguished from the background “noise” of the sample. Relatedly, LLoQ is the lowest relative number of cells that can be detected with acceptable precision (usually between 0.01-0.001% for most assays, as previously mentioned). Both of these are inherently linked to the number and quality of cells we acquire on our instrument.

To illustrate, say that we have an assay that was validated as having an LLoD of 50 cells and LLoQ of 0.01%. To confidently classify a sample with 0.01% abnormal cells as MRD+, we would need to acquire at least 500,000 cells to be above both the LLoD and LLoQ thresholds. If we were to acquire even more cells, for instance 5 million, we could theoretically extend our LLoQ to as low as 0.001% (10⁻⁵). Indeed, a recent MRD validation study by Jum’ah et al. reported that their AML MRD flow cytometry assay achieved LLoQ of 0.01%, with a theoretical lower limit of approximately 0.005% under high event acquisition conditions5. The EuroFlow Consortium’s guidelines for B-ALL MRD detection officially recommend acquiring over 4 million events if this high level of detection is needed4.

Regardless of the theoretical target, detecting MRD at any level of sensitivity starts with a good specimen. Bone marrow aspirate (BMA) is the gold standard for the majority of hematological malignancies, which must be of high quality and not diluted with peripheral blood, a phenomenon commonly referred to as hemodilution. Hemodilution interferes with MRD detection by diluting malignant cells in bone marrow with cells in peripheral blood, which lowers their concentration and can lead to false-negative or misleading results.

Sample integrity, including timely processing and adequate cellularity, is essential for accurate detection1. Instrument performance must also be finely tuned to support this precision: stable lasers, optimal fluorochrome combinations, and accurate compensation are crucial to clearly distinguishing rare malignant cells from normal ones. Finally, proper handling and storage of your sample will help preserve marker expression and ensure reliable MRD assessment.

- Interpretation

Data analysis for MRD assays focuses on distinguishing residual malignant cells from normal regenerating cells using abnormal marker expression patterns. Each hematologic disease has its own immunophenotypic fingerprint, and disease-specific abnormalities are often referred to as LAIPs (leukemia-associated immunophenotypes). Backbone markers (CD45, CD34, CD19, CD3) define broad lineages, while LAIP-associated markers (CD10, CD58, CD81 in B-ALL; CD117, CD123, CD7 in AML) help separate abnormal from normal populations. Aberrant expression such as loss, overexpression, or cross-lineage marker presence is a key clue that defines MRD-positive cells. The analysis requires expert gating or automated algorithms to visualize and confirm these rare populations, ensuring that the detected cells are not artifacts.

Consistent standards for data analysis and interpretation are crucial to guarantee that MRD testing yields comparable results between laboratories and across clinical environments. Organizations such as the European Leukemia Network (ELN) and EuroFlow Consortium develop and refine these standards, integrating data from multicenter trials and both FCM and molecular approaches. Analytical harmonization efforts are focused on aligning panel design, acquisition depth, and gating strategies, while clinical standardization efforts define common thresholds for MRD positivity or negativity.

Together, these steps transform MRD from a technical measurement into a reliable clinical tool for patient management.

Evolving Technologies: Spectral Flow, Computation for data analysis

Tools for detecting MRD continue to evolve, moving beyond conventional flow cytometry toward more advanced platforms such as spectral flow cytometry. Alongside these innovations, computational algorithms are becoming integral for analyzing complex data, enhancing accuracy, and uncovering disease signals that were once difficult to detect.

Spectral Flow Cytometry: This method captures the full emission spectrum of each fluorochrome instead of using fixed channels, allowing larger panels in one tube with less sample volume and better marker resolution. In AML, a single tube 19-color spectral panel matched a 5-tube EuroFlow AML assay and even found new abnormal patterns5.

Computational and Machine Learning (ML) Tools: As panels and event counts grow, manual gating is no longer practical. ML algorithms now help detect rare abnormal populations automatically. Recent studies show transformer-based neural networks, for instance, improve MRD detection in FCM data6.

Summary

In summary, MRD has become an important biomarker with real clinical value. FCM remains central for MRD detection because it is fast, widely available, and gives single-cell-level information. Its accuracy depends on every step, from sample quality and panel design to instrument setup and data analysis. New tools like spectral flow cytometry along with computational analysis, are increasing sensitivity and consistency.

For researchers focused on FCM, immunotherapy, and rare events, MRD brings both technical challenges and new scientific opportunities. It connects residual disease biology with treatment response and patient outcomes. In short, MRD is not just a number; it is a real-time view of how well therapy works.

References

- Szalat, R., Anderson, K., & Munshi, N. (2024). Role of minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Haematologica, 109(7), 2049-2059.

- Heuser, M., Freeman, S. D., Ossenkoppele, G. J., Buccisano, F., Hourigan, C. S., Ngai, L. L., Tettero, J. M., Tisi, M. C., Tobal, K., Tsai, C. H., Venditti, A., Walter, R. B., van der Velden, V. H. J., Wood, B. L., & Schuurhuis, G. J. (2021). 2021 update on measurable residual disease in acute myeloid leukemia: A consensus document from the European Leukemia Net MRD Working Party. Blood, 138(26), 2753–2767.

- Campana, D., & Coustan-Smith, E. (1999). Detection of minimal residual disease in acute leukemia by flow cytometry. Cytometry, 38(4), 139–152.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10440852/ - Chatterjee et al., “Minimal residual disease detection using flow cytometry: applications in acute leukemia,” Medical Journal, Armed Forces India, 2016;72(2):152-156.

- Jum’ah, H. A., Horna, P., Shi, M., Shumway, N. M., Chen, D., Nguyen, P. L., Veltri, L., & Jevremovic, D. (2025). Measurable residual disease analysis by flow cytometry: Assay validation and characterization of 385 consecutive cases of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers, 17(7), 1155.

- Wödlinger, R., Talloen, W., Saeys, Y., & Bodenhofer, U. (2021). Automated identification of cell populations in flow cytometry data with transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.10072.

About the Author

Sanaz Koosha

Sanaz is a Scientist on the Flow Cytometry team at HBRI, based in New York. She joined HBRI in 2023 after completing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. She holds a PhD in Biotechnology from the University of Malaya. Her expertise spans flow cytometry, CAR T-cell therapy development, tumor microenvironment studies, and cancer drug discovery.